Maecenas sed diam eget risus varius blandit sit amet non magna. Nullam id dolor id nibh ultricies vehicula ut id elit. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Morbi leo risus, porta ac consectetur ac, vestibulum at eros. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Curabitur blandit tempus porttitor. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Etiam porta sem malesuada magna mollis euismod. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Donec ullamcorper nulla non metus auctor fringilla. Donec sed odio dui. Nullam quis risus eget urna mollis ornare vel eu leo. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur. Nullam id dolor id nibh ultricies vehicula ut id elit. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum.

All posts by admin

Title 2

Sed posuere consectetur est at lobortis. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Vestibulum id ligula porta felis euismod semper. Maecenas sed diam eget risus varius blandit sit amet non magna. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur. Maecenas sed diam eget risus varius blandit sit amet non magna. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Nullam id dolor id nibh ultricies vehicula ut id elit. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur. Fusce dapibus, tellus ac cursus commodo, tortor mauris condimentum nibh, ut fermentum massa justo sit amet risus. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Nullam quis risus eget urna mollis ornare vel eu leo. Maecenas faucibus mollis interdum. Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Curabitur blandit tempus porttitor. Cras mattis consectetur purus sit amet fermentum. Fusce dapibus, tellus ac cursus commodo, tortor mauris condimentum nibh, ut fermentum massa justo sit amet risus. Cras justo odio, dapibus ac facilisis in, egestas eget quam. Vivamus sagittis lacus vel augue laoreet rutrum faucibus dolor auctor. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue.

Title 1

Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Aenean lacinia bibendum nulla sed consectetur. Donec ullamcorper nulla non metus auctor fringilla. Cras mattis consectetur purus sit amet fermentum. Sed posuere consectetur est at lobortis. Donec sed odio dui. Praesent commodo cursus magna, vel scelerisque nisl consectetur et. Integer posuere erat a ante venenatis dapibus posuere velit aliquet. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Cum sociis natoque penatibus et magnis dis parturient montes, nascetur ridiculus mus. Etiam porta sem malesuada magna mollis euismod. Duis mollis, est non commodo luctus, nisi erat porttitor ligula, eget lacinia odio sem nec elit. Maecenas sed diam eget risus varius blandit sit amet non magna. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum. Aenean eu leo quam. Pellentesque ornare sem lacinia quam venenatis vestibulum. Vestibulum id ligula porta felis euismod semper. Etiam porta sem malesuada magna mollis euismod. Donec id elit non mi porta gravida at eget metus. Nulla vitae elit libero, a pharetra augue.

Stuck in a loop

Os que vão morrer te saúdam, João Pinharanda

OS QUE VÃO MORRER TE SAÚDAM

João Pinharanda, Amarante, 28 de Agosto de 2013

A memória, é o campo de trabalho de Daniel Barroca. Não tanto uma memória individual mas o trabalho lento da memória colectiva; ou ainda, a recuperação, para uma dimensão consciente, dessa memória colectiva, do seu peso. Desde os seus primeiros vídeos (Vestígio, 2002; Verdun, 2003; Saurau, 2003) e desenhos que o artista procura memórias alheias e próximas de proveniência diversa.

Esquecidos e perdidos em sótãos particulares ou vendidos a alfarrabistas, velhos filmes em película (Barulho, 2005), fotografias (Estilhaço, 2005), negativos, existem num limbo difícil de romper – como se, por estarem escondidos, negassem o seu estatuto de imagem, de geradores de informação. Sobre esses materiais estende-se, não um manto de invisibilidade – que implicaria um entendimento leve e angélico do que se esconde; mas estende-se um manto negro – porque se nega informação e se deixa supor que o que se esconde é matéria inquietante.

Há cruzamentos temáticos nestes trabalhos feitos de imagens de guerra e de imagens de família. Sem simplificar nem anular nenhum dos campos temáticos, o artista torna equivalente o estatuto de ambas as realidades: ambas campos de confronto, de equilíbrio e desequilíbrio das partes, de energia e perigo, de euforia e morte, de aliança e ruptura.

Daniel Barroca usa imagens avulsas de cada uma das realidades e devolve-as sem nos enganar acerca da negação a que estavam destinadas. O seu trabalho reconfigura os elementos de uma existência tornada menor deixando, acentuando ou inventando as marcas desse apagamento. É aqui que entra o seu trabalho de desenho e instalação cenográfica.

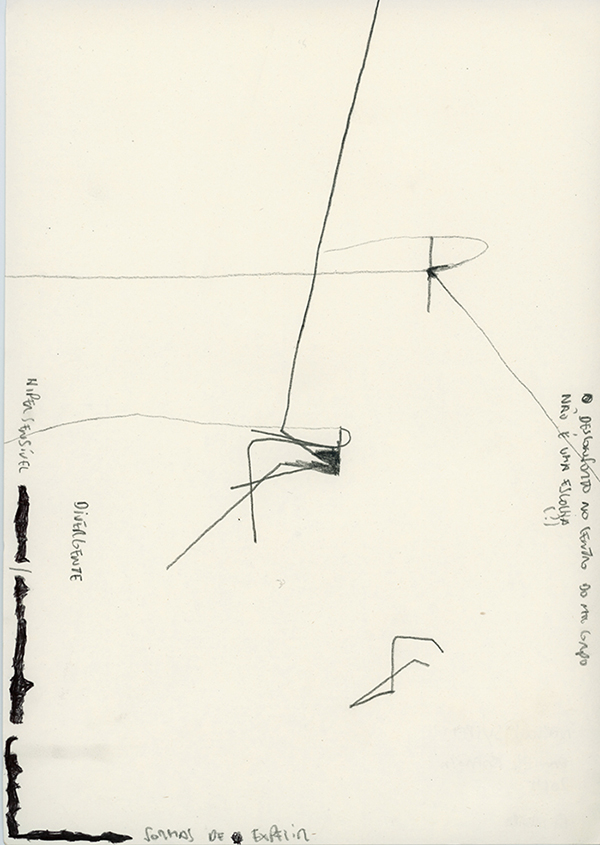

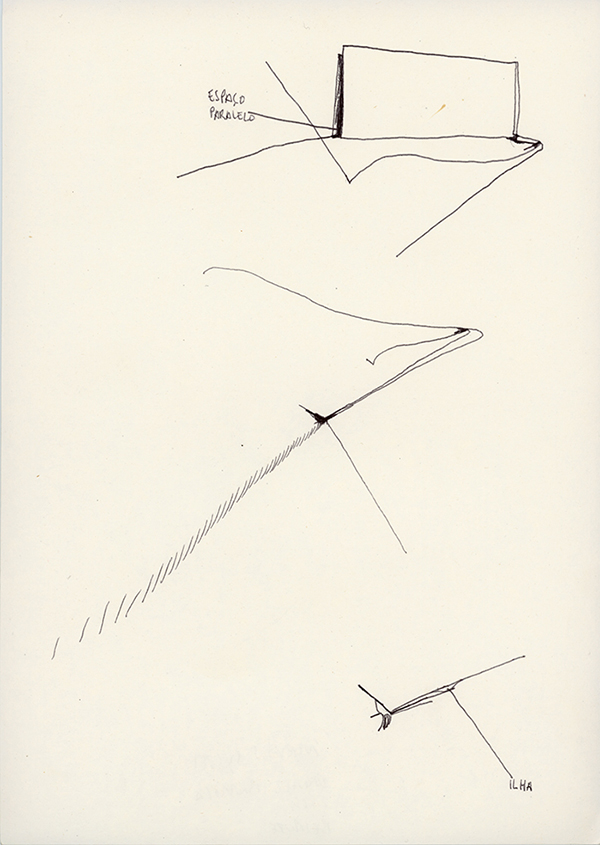

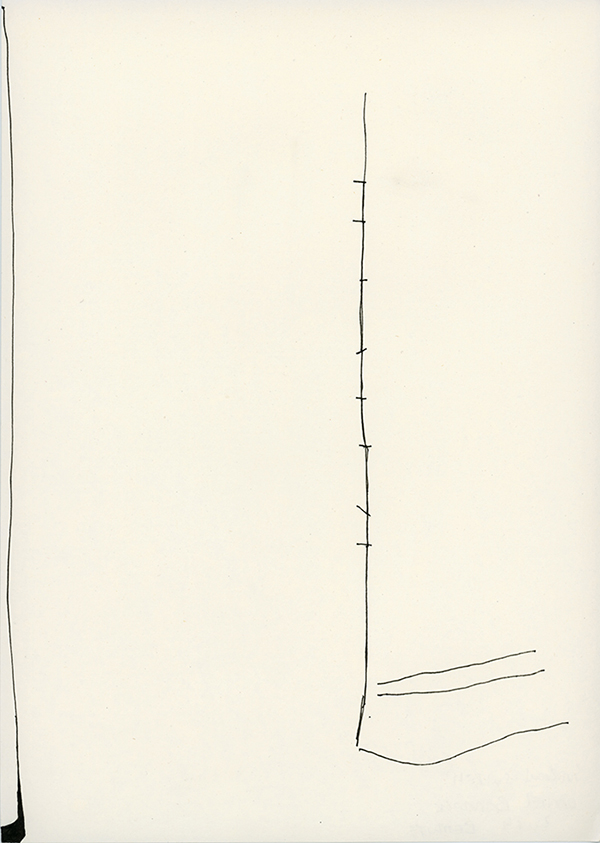

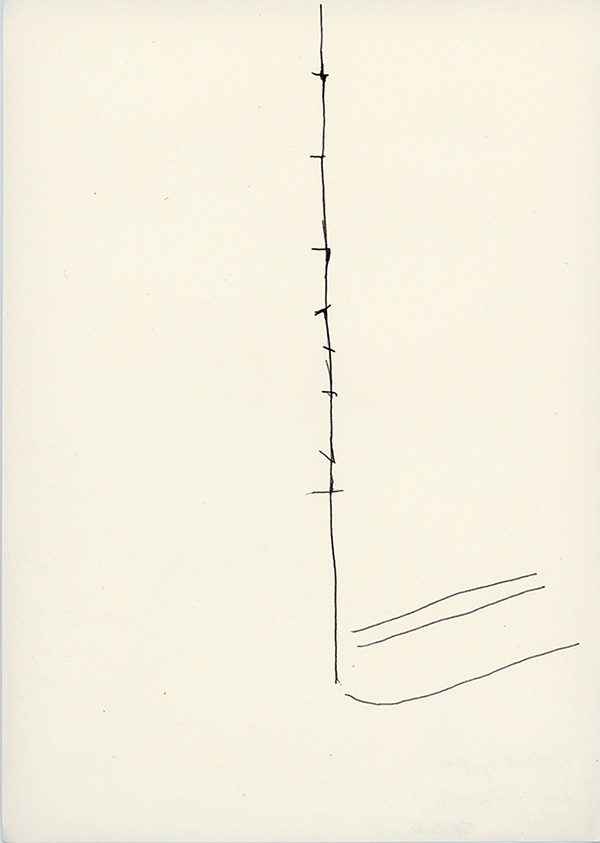

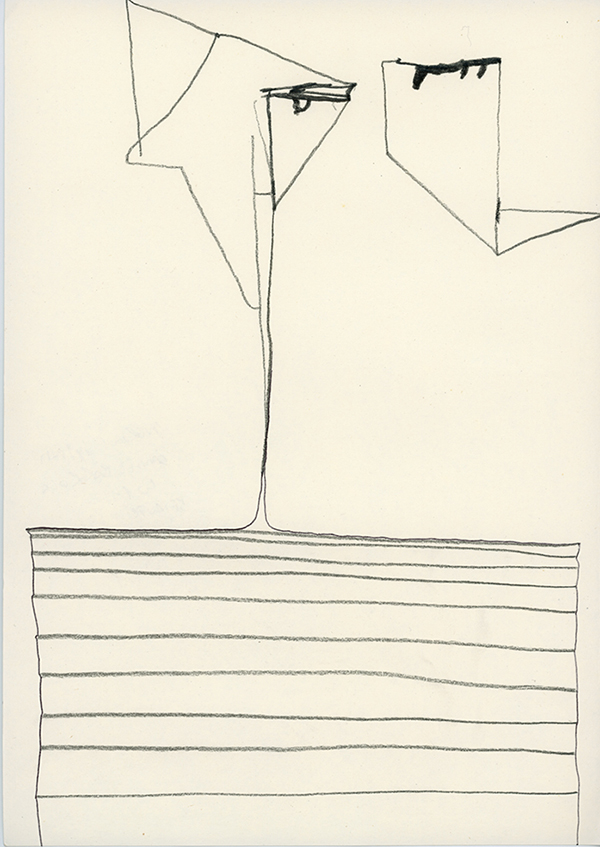

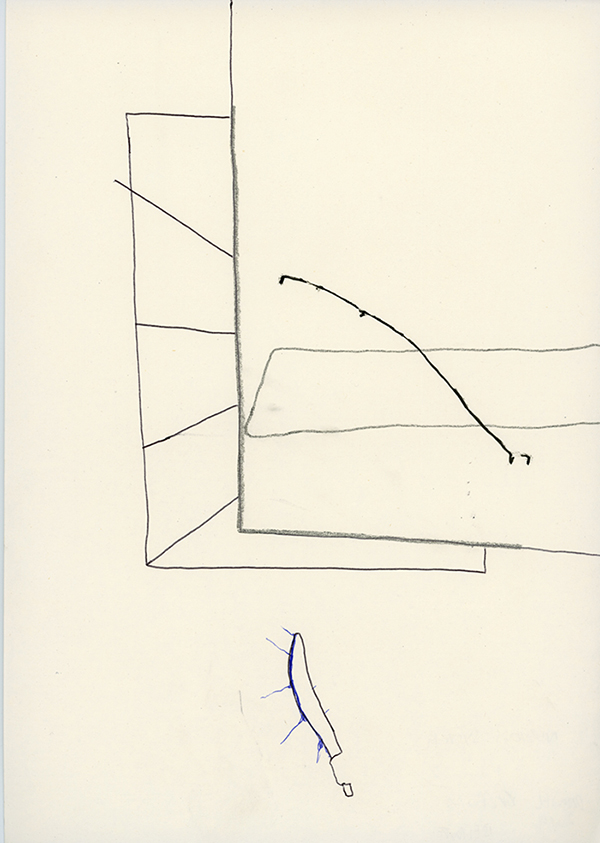

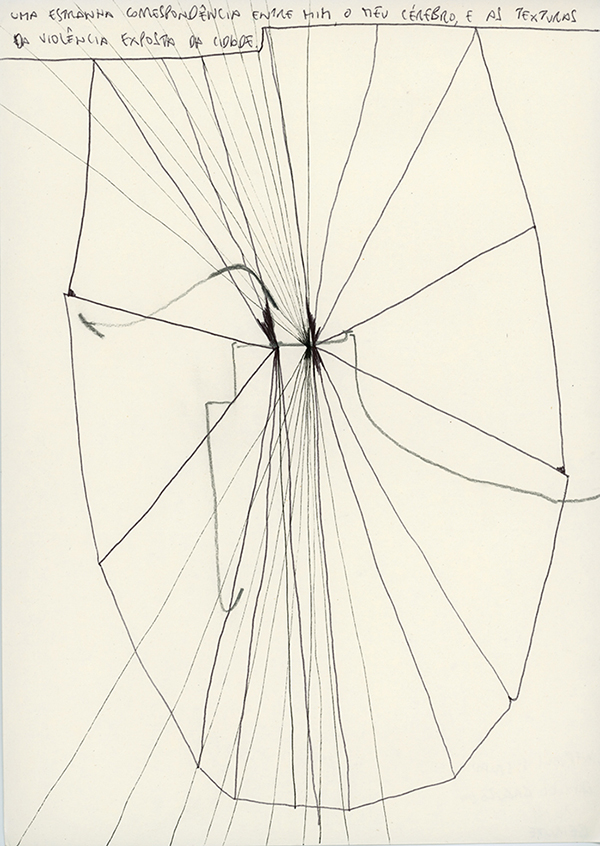

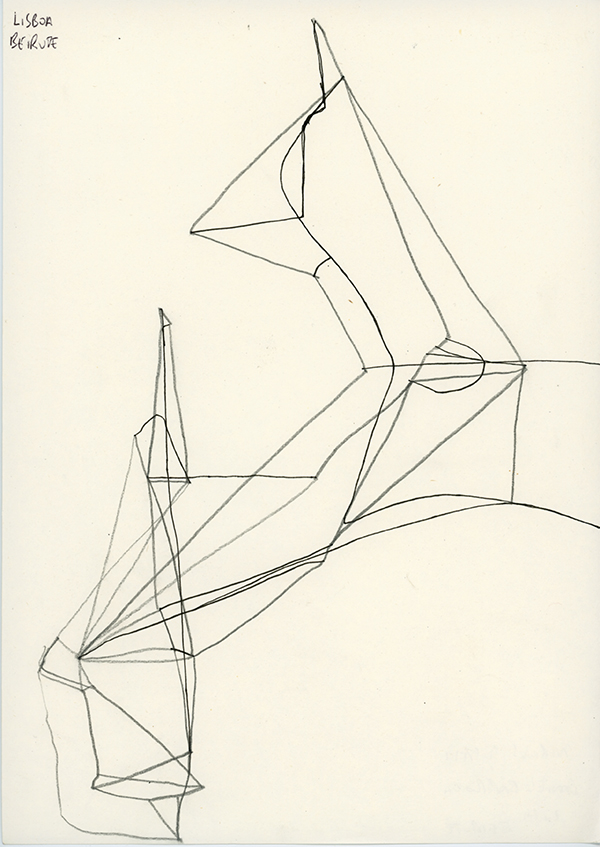

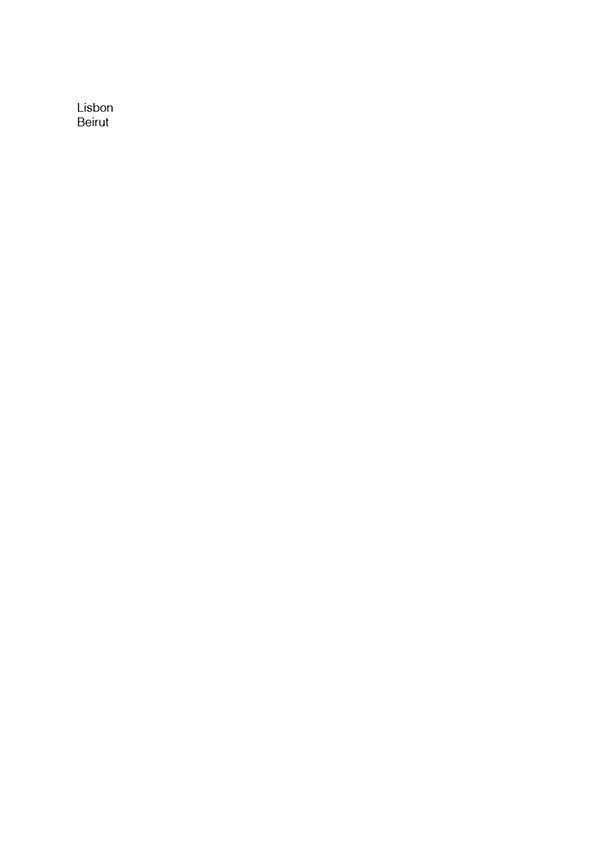

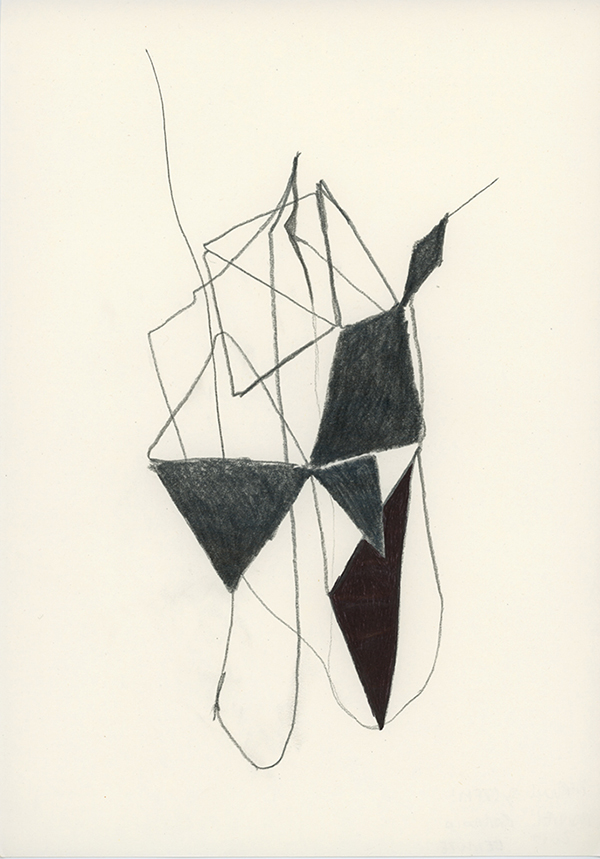

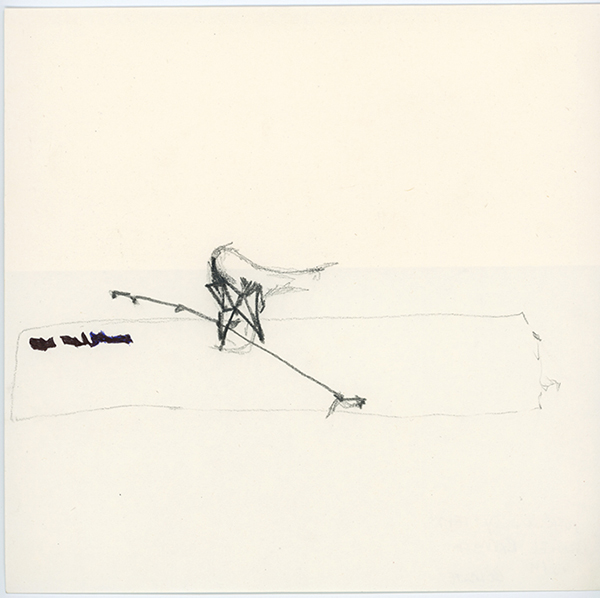

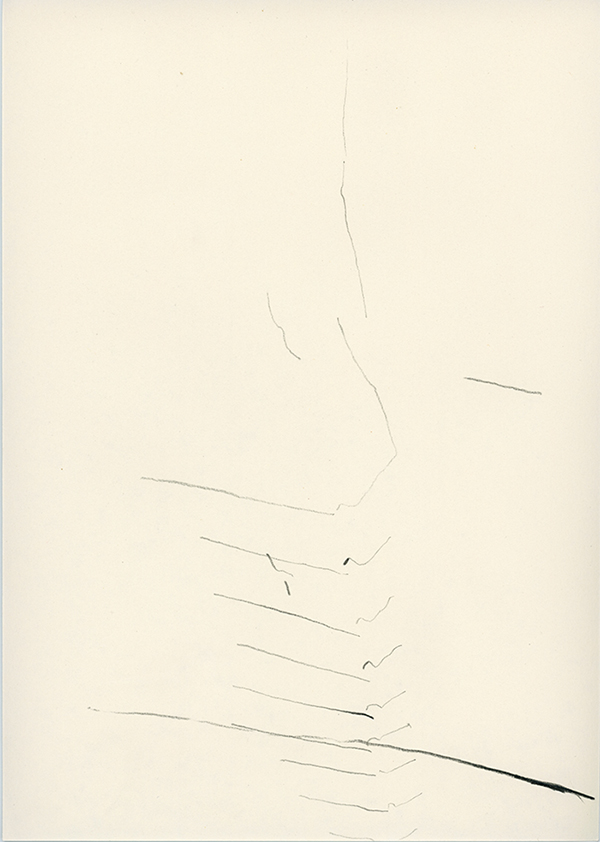

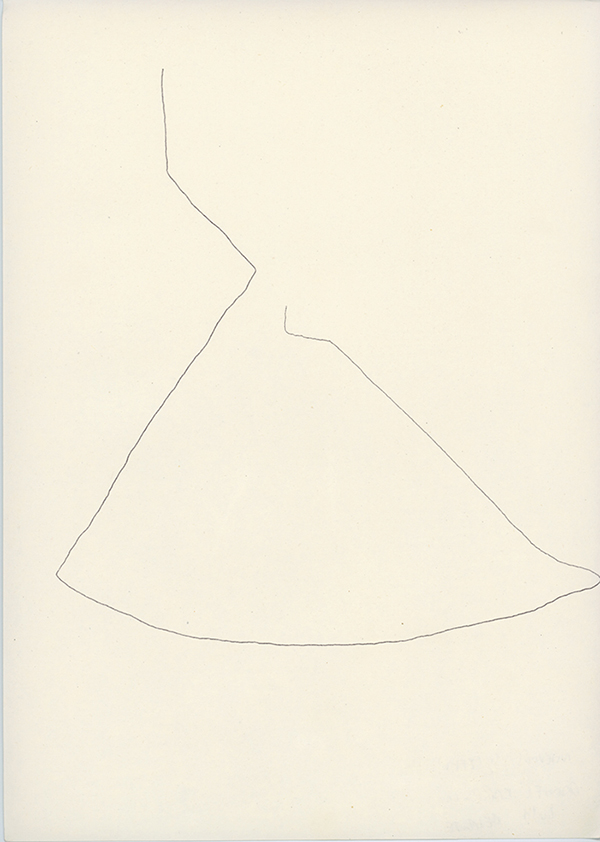

O desenho não é um recurso complementar, mas um modo autónomo que, por vezes, se apresenta em sobreposição às imagens apropriadas e que, outras vezes, ocupa grandes papéis com cristalografias imperfeitas, mapas incertos, sugestão de espaços ambíguos. Em qualquer dos casos o desenho é primitivo, preciso e unificador: As massas de negros tornam-se véus de densidades plurais e, as linhas, elementos de unificação de pontos específicos do olhar. Mas cada vez mais, o desenho se abre em novas soluções, internas e externas: as manchas, raspagens, sobreposições de materiais que lhe são estranhos (como placas de metal com formas geométricas) conduzem-nos, para lógicas de instalação cenográfica (mesas com recipientes e líquidos derramados, agulhas metálicas que materializam linhas e determinam pontos): Porém, em ambas as situações, cumprem sempre a mesma função: unificar, obstruir, revelar o abismo da informação.

Nesta exposição estamos perante um arquivo de fotografias sobre a guerra colonial retiradas de um álbum que era de seu pai. O tema permite a Daniel Barroca colocar-nos perante questões como a camaradagem e a solidão, a euforia colectiva ou o desgaste das relações humanas. E coloca-o a ele perante a luz e a sombra do seu próprio pai. Barroca reconfigura, assim, memórias pessoais e colectivas.

Num momento em que a cena artística portuguesa, uma geração depois do 25 de Abril, aborda finalmente de modo franco, os temas do colonialismo e pós-colonialismo, esta exposição abre mais uma via de reavaliação subjectiva e artística de uma realidade fortemente presente no nosso imaginário comum e no de muitos veteranos e familiares.

Nas imagens, aqueles homens, guerreiros em repouso, confraternizam sem a consciência de qualquer ritualização ou simbolismo, em refeições que podiam ser, sempre, a sua última ceia. E estão ali como os que, em Roma, preparando-se para entrar na arena, se dispunham a entregar a sua vida ao imperador. Ao resgatar do esquecimento cada uma destas imagens, Daniel Barroca está a reconfigurar realidades de protagonistas e de tempos passados que se sobrepõem a protagonistas e a tempos presentes – e assim tece uma complexa rede de perguntas sobre a vida e a morte, a certeza e o erro, o individual e o colectivo, a opressão e a liberdade.

Dripping Hand, Fernando Poeiras

Dripping Hand

Fernando Poeiras, 2010

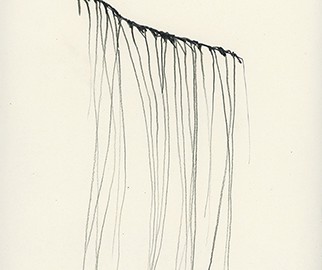

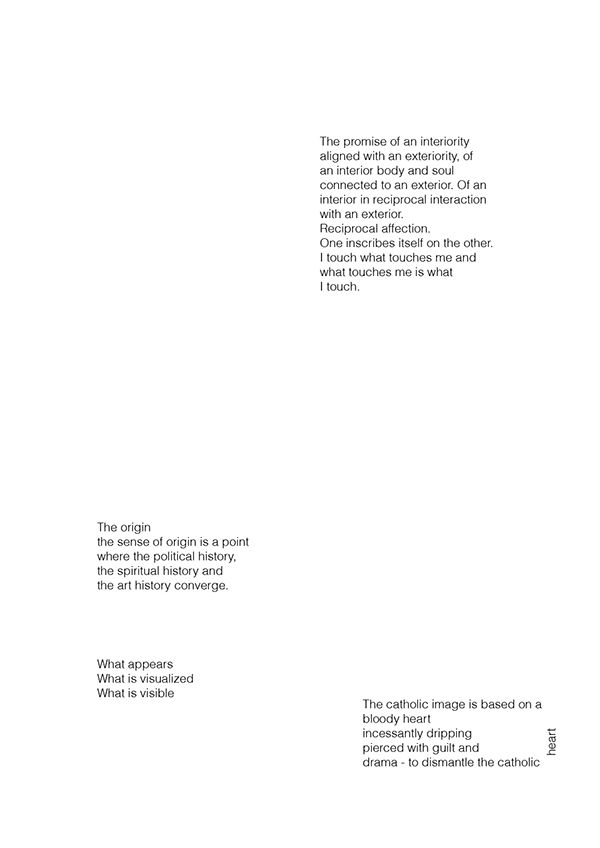

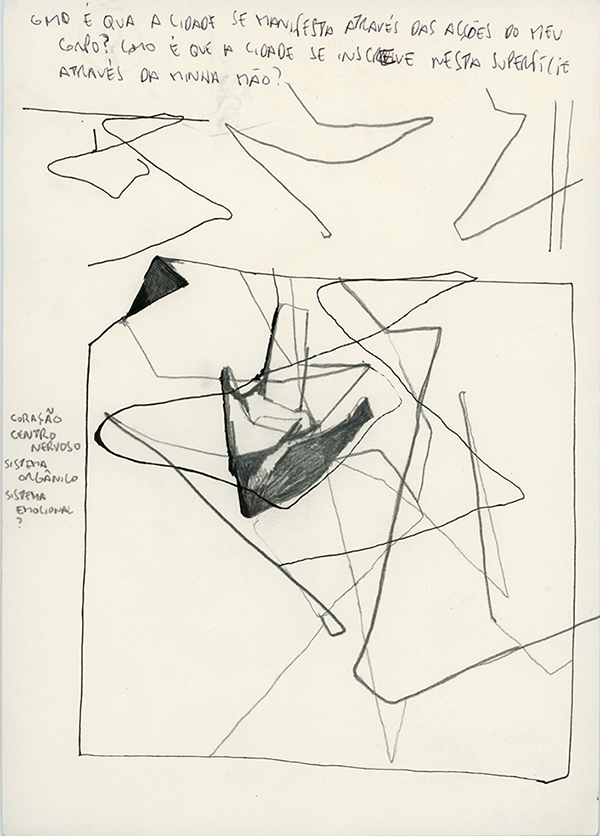

1. Primeira aproximação: o nome aponta para uma acção-objecto – acção instalada e acção sofrida. Mas, “dripping hand” é um fragmento, e um fragmento subtraído e diferido, naquilo que é “enunciado” nesta imagem-vídeo de Daniel Barroca: registo (subjectivo) de um acontecimento (alegórico) (instalado).

2. Movimento de concentração: a acção sofrida. Dripping hand descobre a co-materialidade entre um drama de destruição e as forças físicas a operarem nesta construção: erosão, gravidade, resistência e atrito. A substância dramática da peça não é recolhida no movimento cíclico da vida, ou na morte, seja a morte natural ou dada, mas numa acção, ou dramaturgia, física. No movimento físico da destruição consome-se a “alegoria” (e os seus múltiplos sentidos). Física elementar niilista.

3. Movimento (in)diferido: a (im)possível reprodução. As formas do “registo” remetem normalmente para a construção do lugar “neutral” do espectador face a um objecto, desejavelmente na retórica do apagamento do espectador. A “documentação” do acontecimento dripping hand é atravessada pela presença de um olhar incorporado: câmara subjectiva ou construção do corpo-câmara em que o olhar segue o acontecimento – o movimento de destruição – e é vibrado pelos movimentos da presença do corpo: movimentos instáveis, movimentos de regulação da proximidade e vertigem. Estatuto paradoxal deste “espectador”: “reprodução” visual do acontecimento sofrendo as acções e reacções do corpo próprio.

4. Estação 1: nós: segundos “espectadores” de Dripping Hand. Nós somos o último elo nesta cadeia – montado pelo autor – de subtracção e diferimento. O que chega até nós? Se a pergunta pode ter lugar é porque Dripping Hand não se consume na positividade da sua ambígua construção vídeo. Possuímos a experiência que a obra constrói – e não nos é dada outra – que é também a experiência de uma ausência. Chegam-nos apenas fragmentos, escombros, restos e sobretudo a consciência sensível dos filtros… Na teoria estética muito tem sido escrito sobre a posição – de vários modos – privilegiada de liberdade e juízo do contemplador. A obra do Daniel Barroca faz-nos permanentemente suspeitar desse lugar “exterior” ao qual a “presença” sempre se subtrai e difere.

5. Estação 2: nós: ironias da contingência. O som directo capta simultaneamente China Girl – com função de fundo ambiente de trabalho, som “deslocado” de uma função no trabalho – e os movimentos ruidosos das acções desencadeadas no trabalho – função de registo. Assim, na construção vídeo, ao espectador chega uma única imagem sonora – em “registo duplo” – mas que opera um permanente des/fasamento com a “imagem”.

6. Vertigem: estamos no meio. Dripping Hand constrói-se sobretudo na “mise en abyme” de espaços, de meios de trabalho, e de corpos, das acções do e sobre os corpos. Envolvendo a imagem – e usamos a palavra “imagem” apenas para simbolizar a rede de relações construídas – há um afecto de desolação, de assolação trágica. Talvez a visão que alimente o trabalho de Daniel Barroca seja a de que o mundo é – ou é esse o seu estado – um limbo e o artista o (des)fazedor de velaturas. Paradoxo do artista, ou talvez, a sua pequena falta de congruência: seria preciso construir para expor essa condição destrutiva.

Circular Experience, Beniamino Foschini

CIRCULAR EXPERIENCE

Beniamino Foschini, Turin, September, 2009

In The Sleepers, Daniel Barroca sets up a meta-narration made up of signs which transmute themselves into an open allegory. The exhibition is centred on the video installation … a hazed and confused landscape, as the last passage of an ideal path which starts with Verdun (2003) and continues with Soldier playing with a dead lizard (2008). The artist carries on and goes deeper into the questions of the manipulation of the found object – either photographic or filmic – and of the linguistic refoundation of form and meaning. … a hazed and confused landscape is based on an 8mm original movie, a German propaganda document about the invasion of Crete by the Wehrmacht in May 1941. The video gains a new horizon of sense: from a condition of abandonment – the film was discovered in a flea-market in Berlin – through a meditation on language and on “other” possibilities, existential and aesthetical. An anonymous document – in its official historical value – gains the status of a necessary source, when it is found and re-elaborated through the artist’s filter.

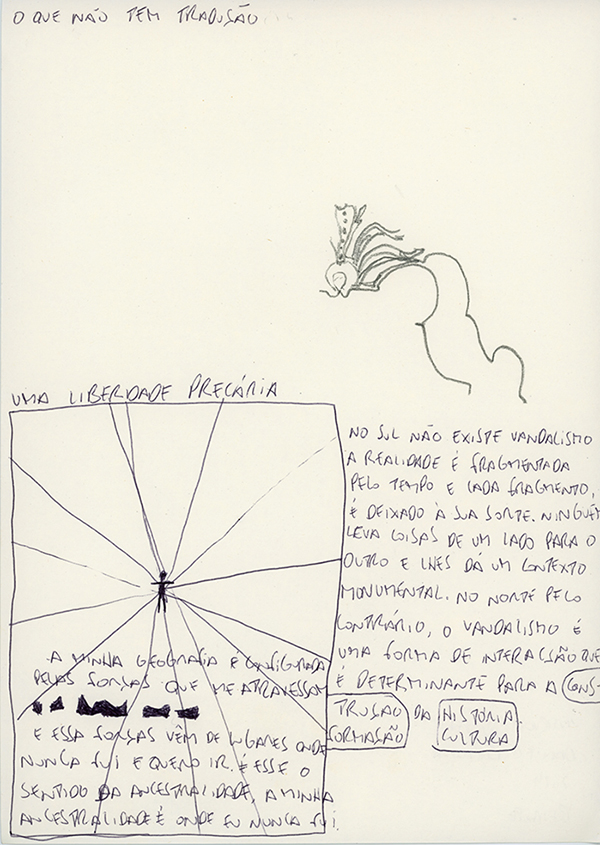

A meditation on History – as the field of collective memory and therefore of shared identity – is the core of these series of works. History is a cauldron, but not of styles one can cling to. It is rather an assembly of events, apparently marginal, that establish an interpretative discourse aiming to be wide and critical about our present, while flowing through the hypothetical great narration.

Thinking about a dominant way of interpreting History reminds me of Paul Klee’s painting Angelus Novus, as interpreted by Walter Benjamin in the ninth of his theses Über den Begriff der Geschichte. The Angel of History hovers with eyes wide open over the ruins of the past, violently transported by the wind of progress. He is a tragic and totemic figure of the relationship between humankind and its past. A prophetic and lyrical vision of the German philosopher of the present and near future – the theses were published in Spring 1940 –, it is a warning against progress and the contradictions of linear History. The act of pointing is inherent to the substance of the found object and thus it offers the privilege of recovering the fragments of History in order to give to the subject a more universal (and therefore a more doubtful) sense.

At this point, one may consider Barroca’s work from a more specific point of view and especially from an aesthetical one. It shows constantly a sense of precariousness, of standstill on the brink of a cliff. The work never gives itself as an accomplished object, neither as a concrete epiphany nor as a simulacrum. The work gives itself as a filter – as a further filter besides the vision of the artist – as a veil between what it is – the subject of the work – and the observer. Let me consider some previous works, for instance the Lama series (2007). They are focused on manual work, on concrection, on matter, but we never see the final result. On the contrary, we see its own crystallization onto a photographic support. Questioning the notion of authoriality does not simply imply a reflection on the origin of the work of art – the found object in this case – but on how and why the artist gives shape to a vision and conveys its latent content.

Thus, in Barroca’s research the found object is an excuse, an occasion. It does not belong to the notion of archive, of a Warburgian atlas which appears to be today of great appeal among his generation. Furthermore, it is not the paratactic juxtaposition of images that gives value to the subject. Value is rather given by the manipulation and the refoundation of images due to a process of subtle and critical linguistic transformation.

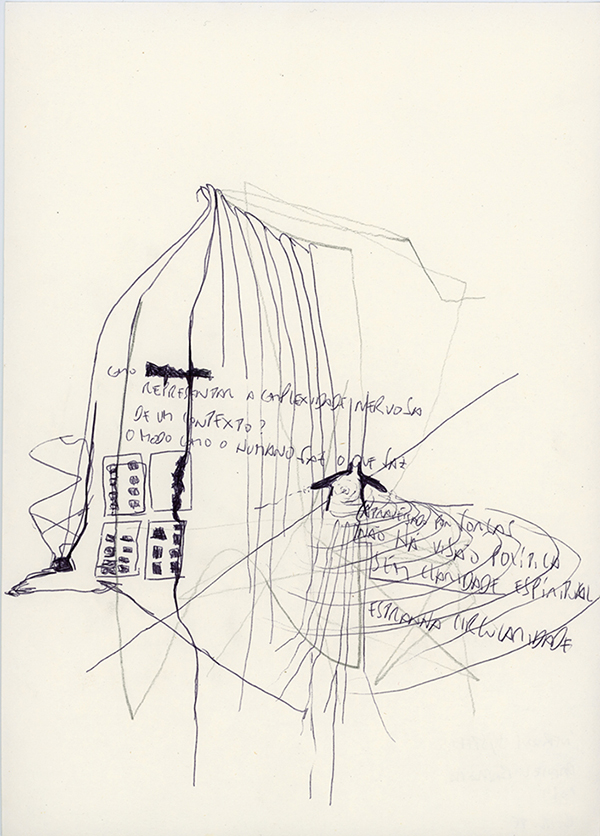

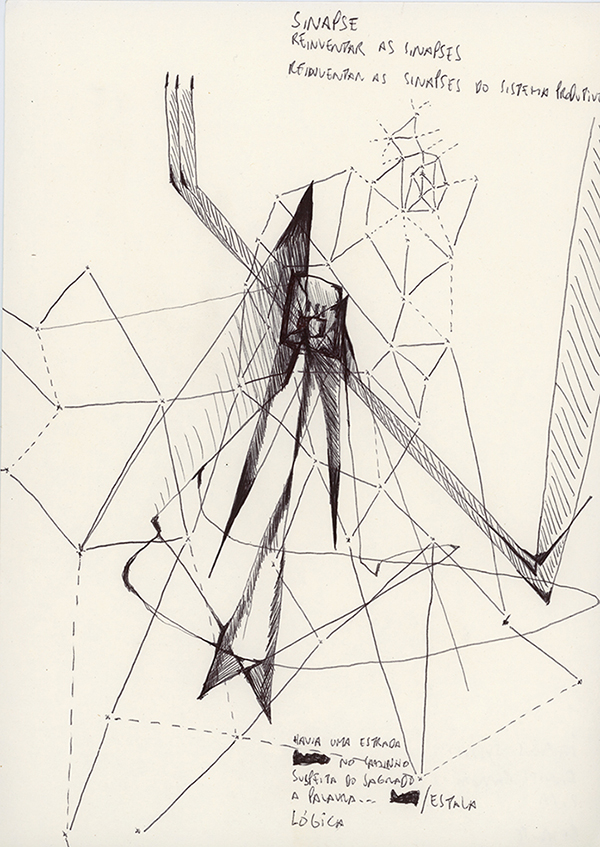

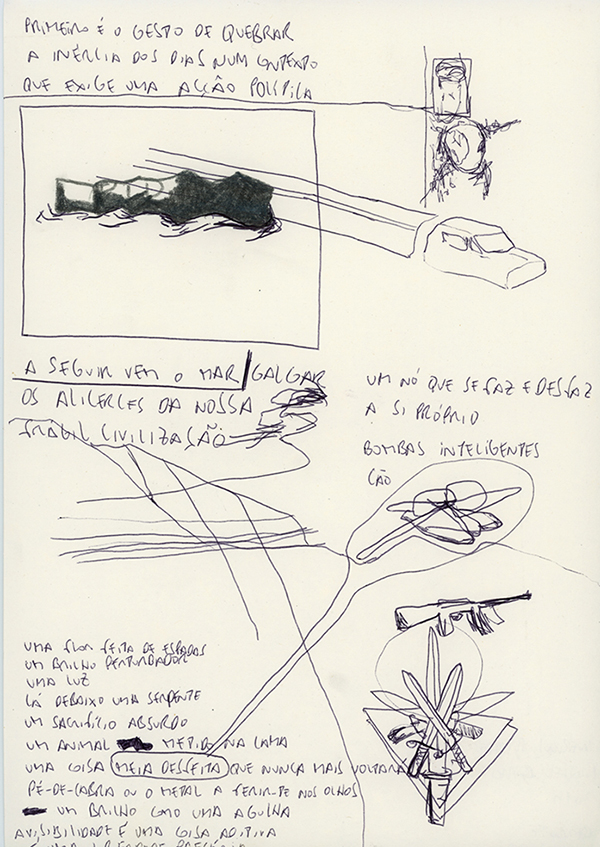

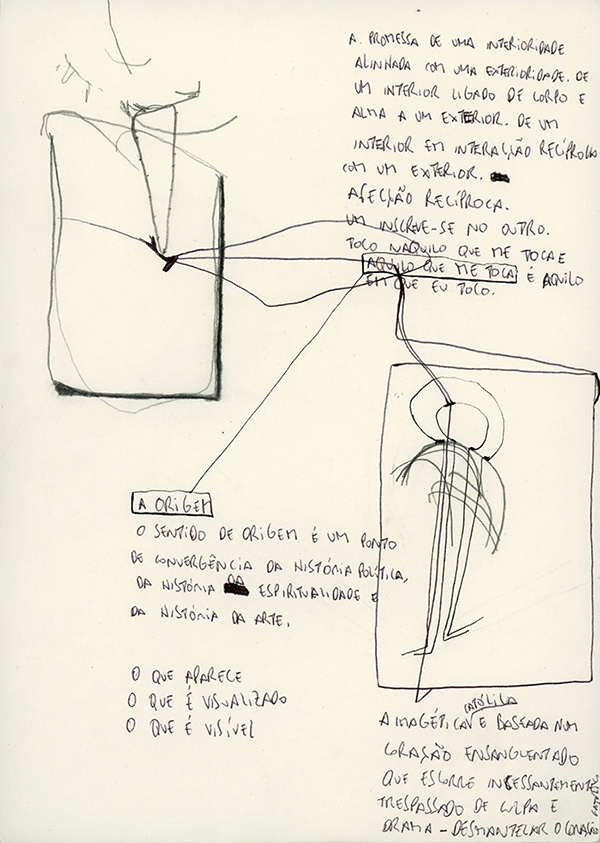

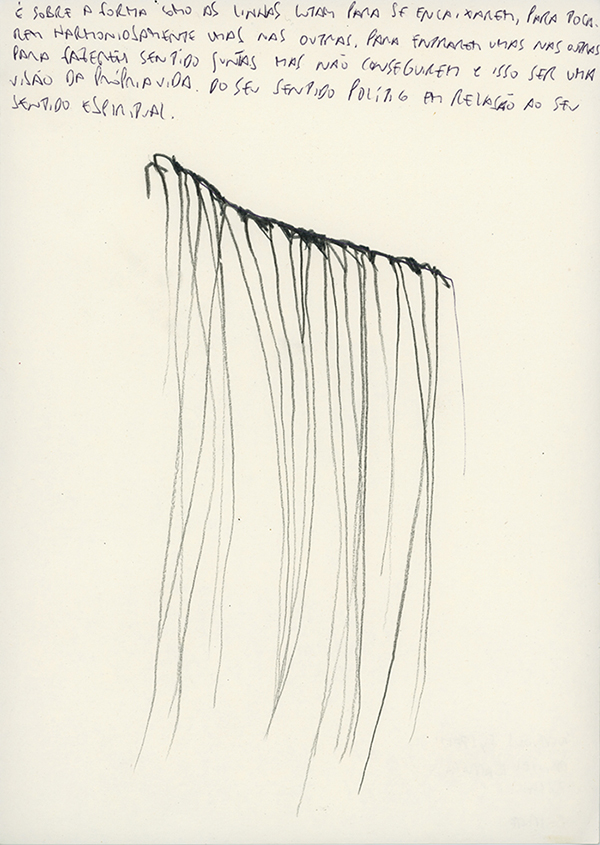

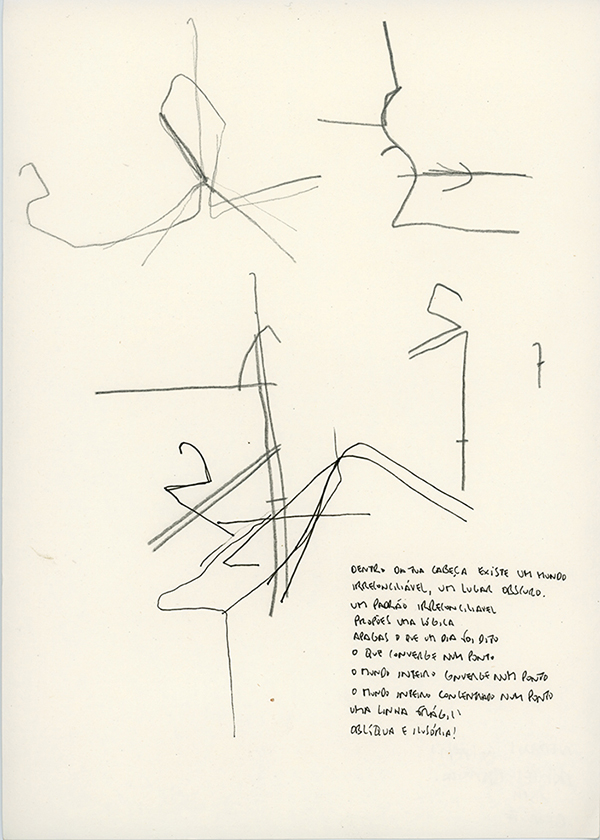

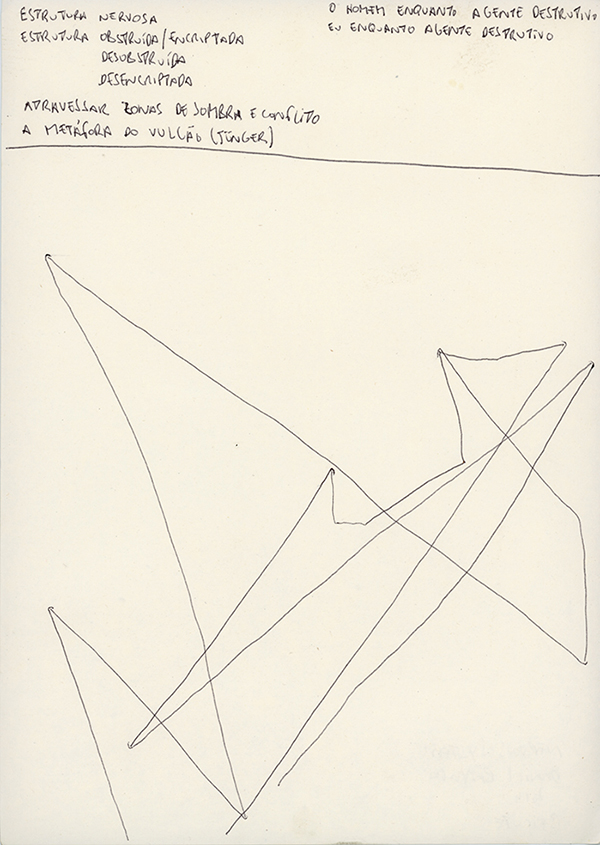

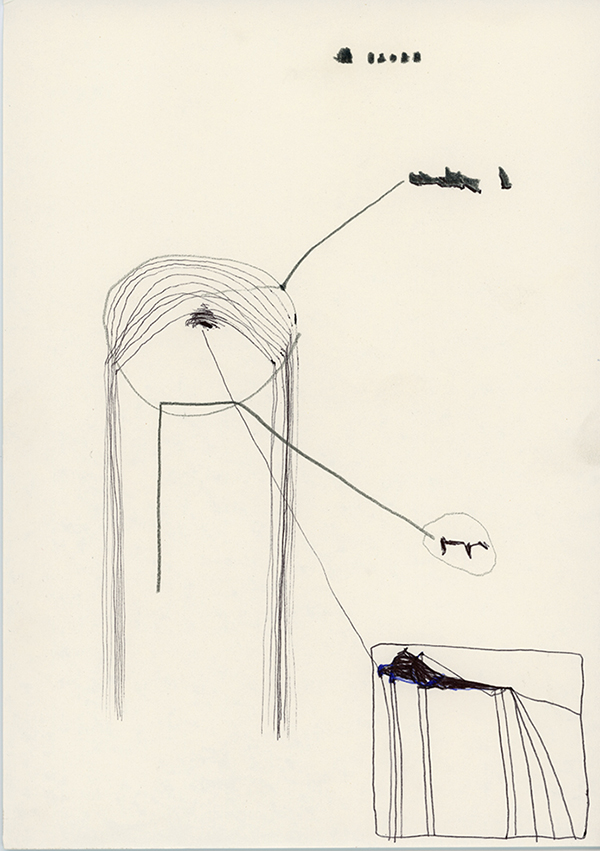

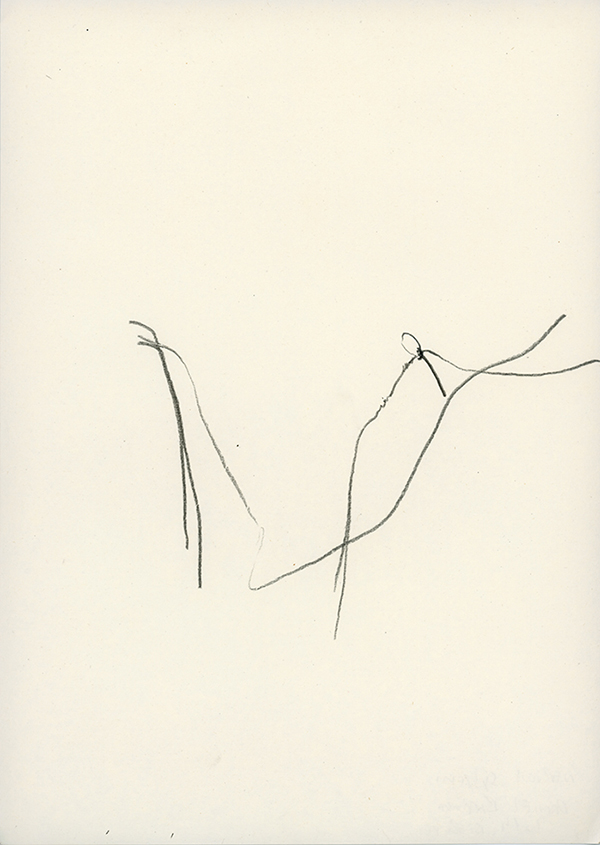

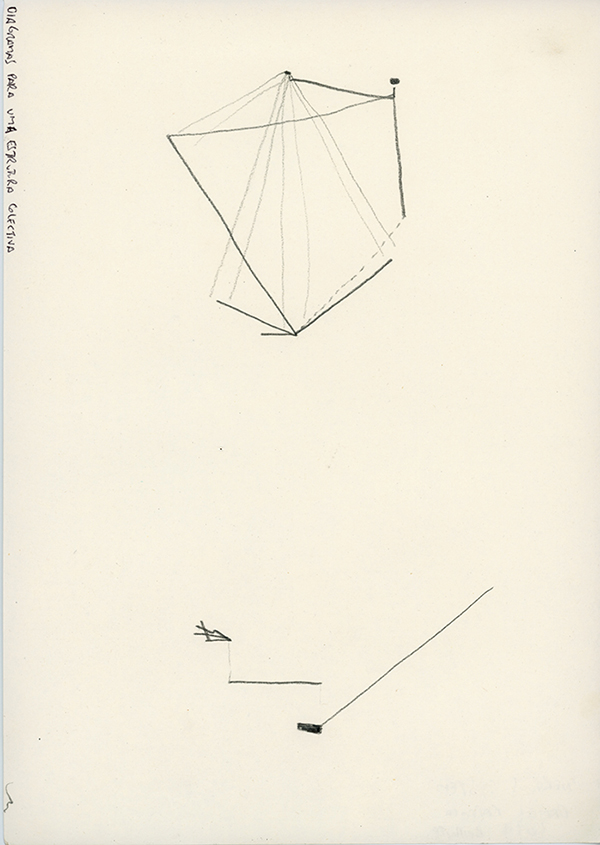

The critical attitude of Barroca’s works is not primarily a socio-political one. The field of interest is still the image: for this reason, it is interesting to analyze the drawings that usually accompany his installations. They are not preparatory sketches, nor do they represent a logical argument on the notion of drawing. They show a manual need in the creation of the work that goes beyond the manipulatory one in the making of the video. It is the underlining of an alternate process between two different languages, which will become synchronic because they play on the same field.

Does not drawing – as an artistic technique – represent the daily discipline of thinking and making art? Barroca puts in this series, entitled The Sleepers, the whole experience of exhibiting in order to suggest its illogic and intuitive journey as an artistic process – not to underline didactically its planning. In this way he is able to transfer onto two different levels the role of the artist as “author”, as manipulator and as artificer.

Here the artist grafts two figures poised between history and legend, Western and Eastern Europe, who mystically represent a popular need of rebirth in periods of crisis. On one side we have D. Sebastião, the child king of Portugal, the last of the Avis dynasty, defeated in 1578 by the Moors in Morocco while he was trying to conquer it and then gone missing; on the other side, Constantine Palaiologos, last emperor of the Byzantines, killed during the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Both being “sleeping kings”, after their deaths they were surrounded by a messianic halo as saviour characters who would come back in the moment of need from their state of sleep, from fog or marble. These kind of suggestions become mixed together in the experience of knowledge made by the artist, and appear cyclic and periodic.

At the same time this circularity – which means also a constant return of the artist to what happened and to what will happen, in a short circuit way – reverberates on a system of circular walks which usually outline tangential lines: the hic et nunc of the exhibition is a moment of passage during an uninterrupted flow of stimulations and sensations. It is neither an harbour nor the conclusion of a process, but rather a stage of the liquid laboratory Nicolas Bourriaud attempted to define in the aesthetics of cluster inside his altermodern project.

Just as in an allegory, Barroca does not want to give answers, rather open horizons of reflection through the force of the image and of its potential critic charge.

Dry Traces, Radhika Khimji

Dry traces

Radhika Khimji, 2009

Daniel Barroca’s varied practice is based on an archive of found images. The artist collects photographs from various sources to reuse them to make films, books, slides and sculptures. Barroca’s method of reworking intentionally ruptures the images away from their found places. These historic documents are not reshaped into a complete comprehensive narrative, instead the images are treated, censored, made double and split. By fragmenting a fragment from his archive, Barroca makes the found past present by drawing over it. There is an interchange between the historic archive and the artist’s personal landscape, which is meshed together to produce a fragmented image relating always to the moment of its making.

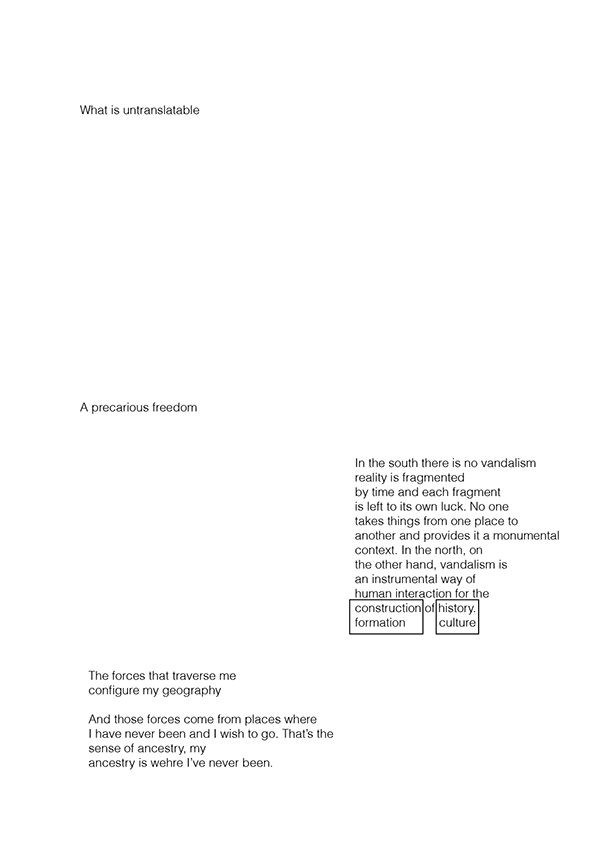

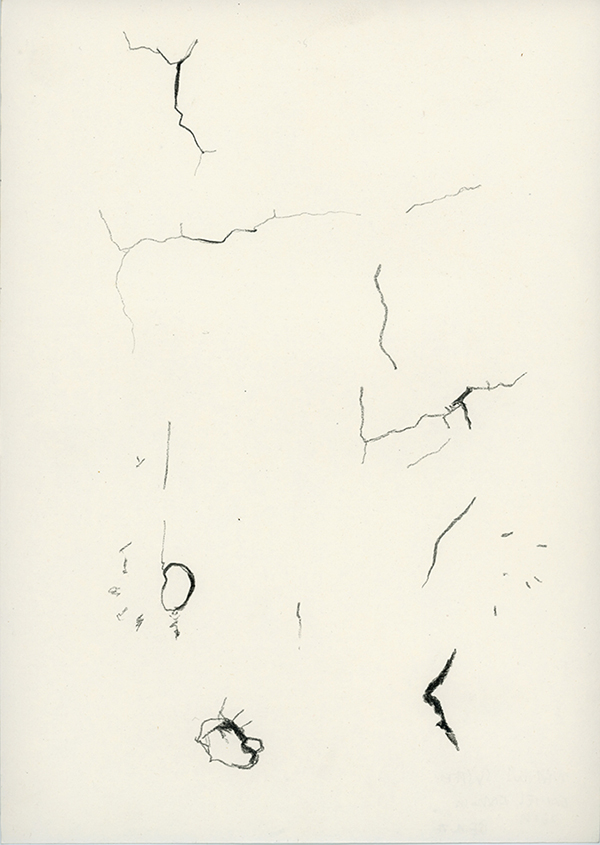

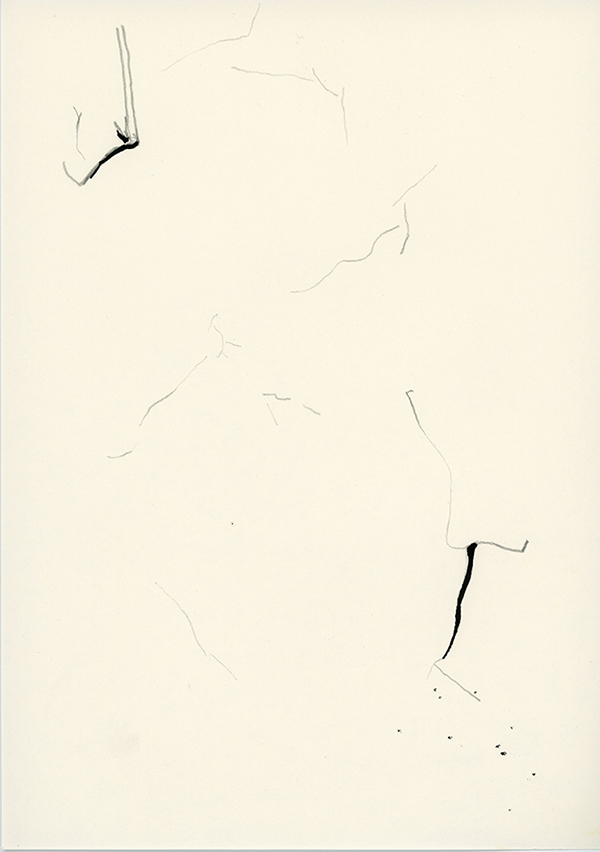

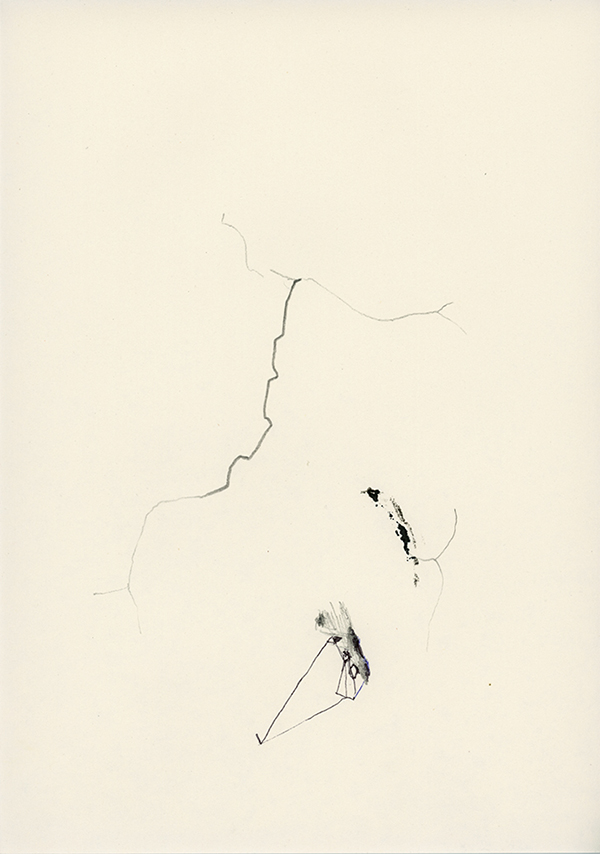

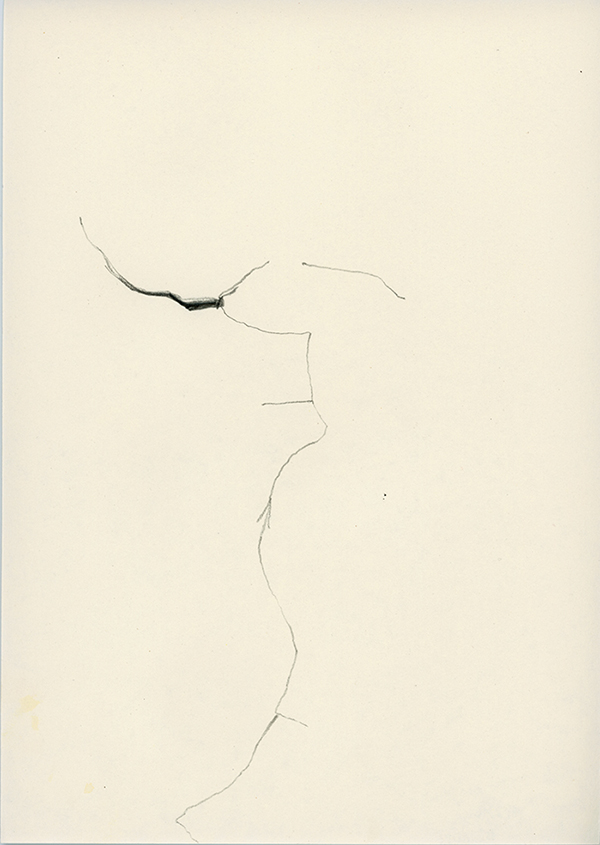

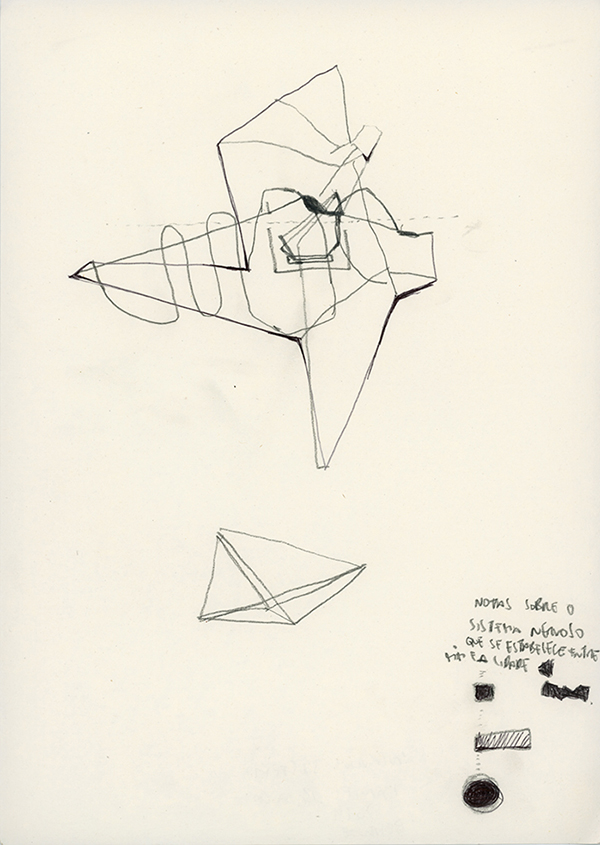

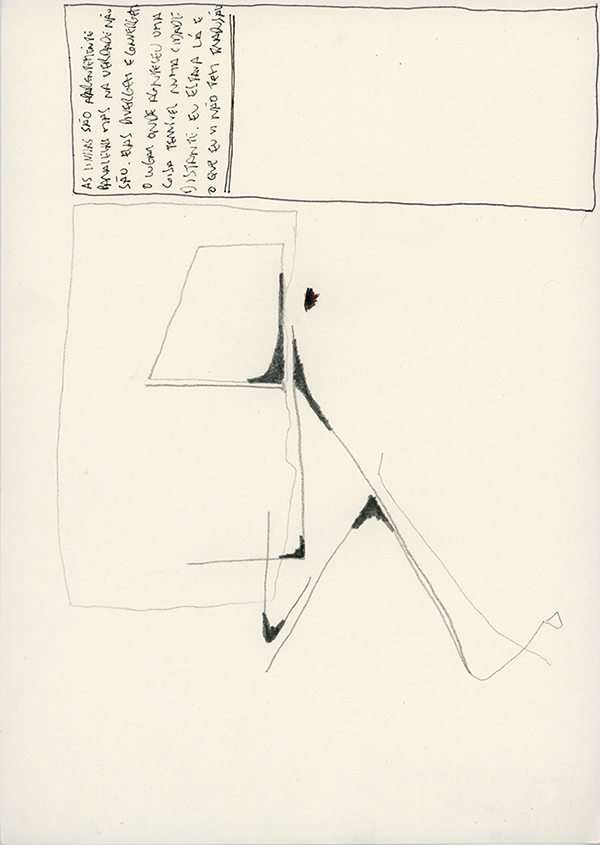

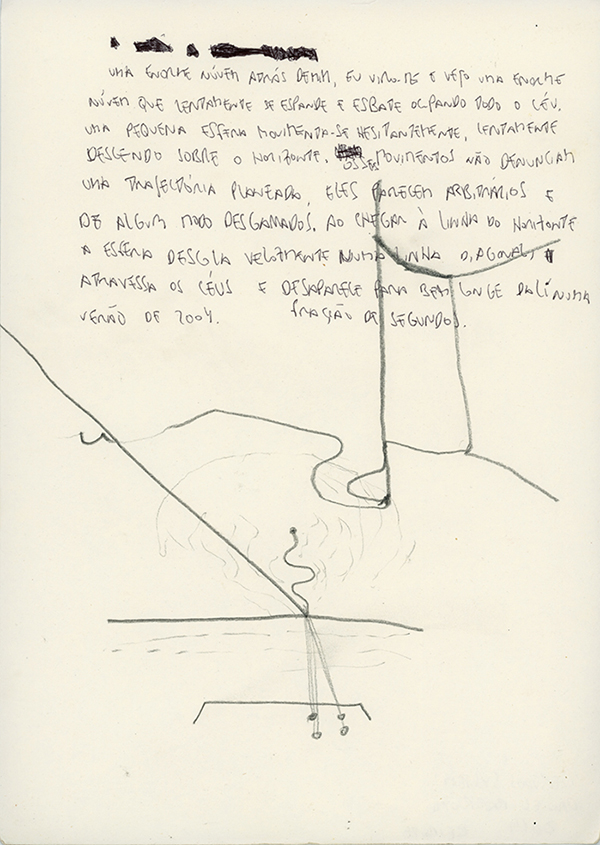

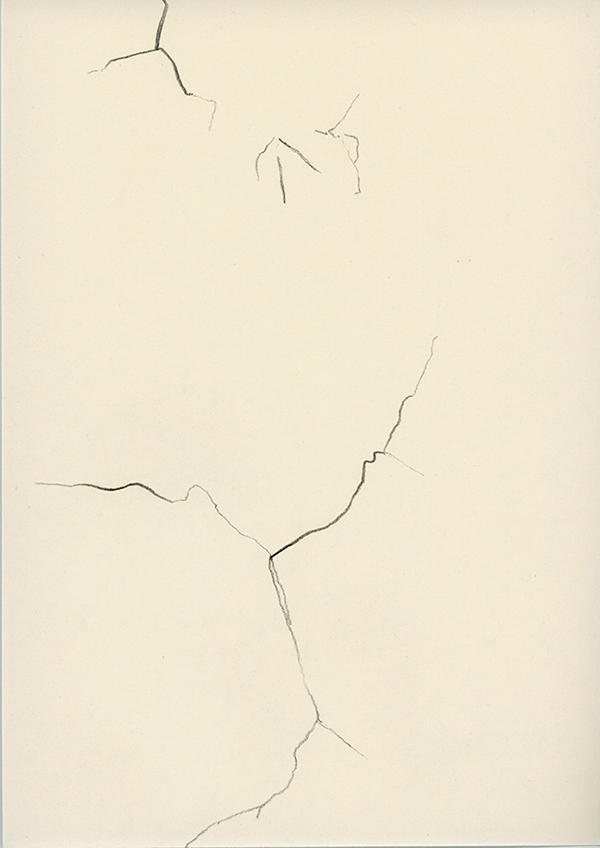

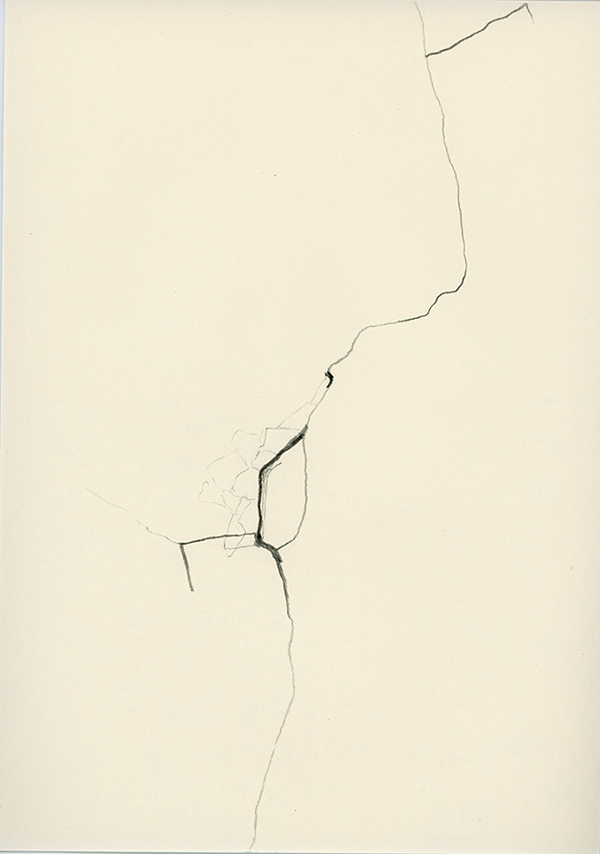

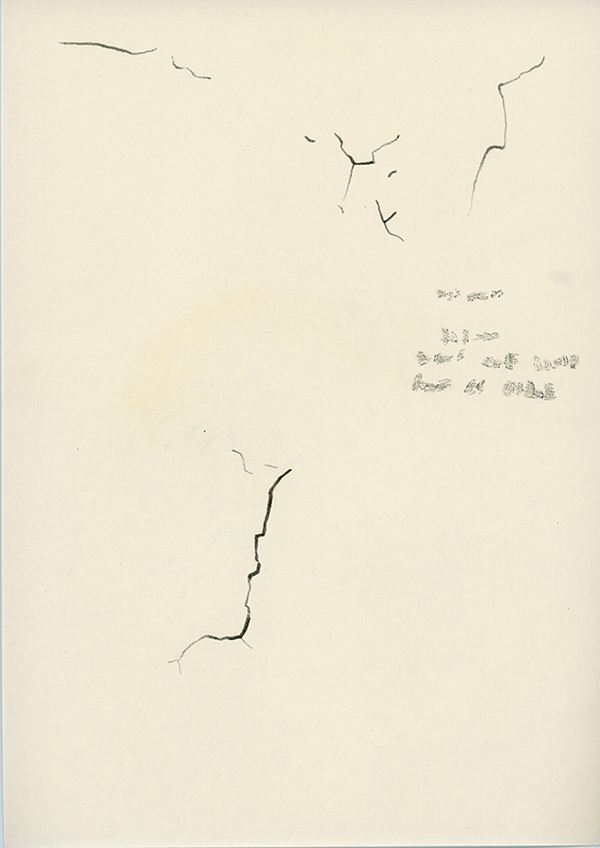

Barroca’s drawings enact a similar search for a disembodied space. A search over an overlapping surface which separates and has a sequential rhythm of its own. The notebook format allows for this seeking, which is fragmented through its own production. By turning pages, a drawing made of charcoal smudges a little and impresses its corresponding page with its image. This doubling adds to the image in these drawings where solid shapes cross the middle of a page. These traces and outlines, map out a spatial trajectory manifested through their own process. The subject is emptied and dried out of the work, so that one is left with a skin; a surface made active by marks made of ink, pencil and charcoal and some pigment. The ink dries out on the surface of the paper leaving behind a brittle surface. A dry fragmented process that animates itself on a page.

These drawings describe spaces, places and beings that cannot be named. They are fragments from lost histories which now exist as gestures and marks made to reside on the edge of description and resemblance. The work is a collection of mapped out spaces which do not “recompose the past with presents.”[1] but are caught in a state of becoming.

[1]Deleuze, Gilles, Bergsonism, trans. Tomlinson, Hugh and Habberjam, Barbara, New York, Zone Books, 1991, pp. 57-58

Dry Traces

Radhika Khimji, 2009

A prática artística de Daniel Barroca baseia-se num arquivo de imagens encontradas. O artista colecciona fotografias de várias proveniências que reutiliza para fazer filmes, livros, slides e esculturas. O seu método de retrabalhar as imagens rompe intencionalmente a ligação que estas à partida têm com o seu lugar de origem. O aspecto destes documentos históricos não é refeito no sentido de uma completa compreensão narrativa, no lugar disso, as imagens são tratadas, censuradas, duplicadas e cortadas. Ao fragmentar um fragmento do seu arquivo, desenhando sobre ele, Barroca, faz do passado encontrado presente. Existe um cruzamento entre o arquivo histórico e a paisagem pessoal do artista, esta mistura produz uma imagem fragmentada que remete sempre para o seu fazer.

De um modo semelhante, estes desenhos de Barroca, constituem a procura de um espaço desincorporado. Uma procura sobre uma superfície que separa e se sobrepõe a outra compondo um ritmo sequencial próprio. O formato do livro de apontamentos permite esta busca que é fragmentada através da sua própria produção. Ao passar as páginas, um desenho feito de carvão borra ligeiramente e impressiona a página oposta com a sua imagem. Esta duplicação adiciona-se às imagens desenhadas nas quais formas sólidas atravessam o centro das páginas. Estes rastos e estes contornos, mapeiam uma trajectória espacial que se manifesta através do seu próprio processo. O objecto é esvaziado e seco durante o processo de trabalho de modo a ser-lhe deixada apenas uma pele; uma superfície activada por marcas de tinta, lápis, carvão e algum pigmento. Ao secar sobre o papel a tinta deixa para atrás uma superfície britada. Um processo a seco e fragmentário que se anima a si próprio sobre uma página.

Estes desenhos descrevem espaços, lugares e seres que não podem ser nomeados. São fragmentos de histórias perdidas que agora existem enquanto gestos e marcas feitas para residirem no limite da descrição e da semelhança. O trabalho é uma colecção de espaços mapeados que não “recompõem o passado com presentes.”[2] mas que são apanhados num estado de devir.

[2] Deleuze, Gilles, Bergsonism, trans. Tomlinson, Hugh and Habberjam, Barbara, New York, Zone Books, 1991, pp. 57-58

New Memories, Francesco Stocchi

NEW MEMORIES

Francesco Stocchi, 2008

translated by Stefano Cagol

The world of Daniel Barroca is inhabited by suspended presences that oscillate between present and past, indeterminate but carrying an image. Barroca’s research appears to deal with the relationship between form and image, with the latter enshrined in the evanescence of the former. His work distinguishes itself by the absence of a solution, having no end but an aim. It is not interested in right or wrong but merely truth, constructing an endless cycle informed by the artist’s mind and dictated both by his own exigency and by those presences that inhabit his world – a world made of new repetitions, temporal illusions, divides, details and echoes. His recordings are visual and aural echoes of uncertain origin that may never have been pronounced, reminiscences of something that may never have happened. The real and unreal merge in a single memory that becomes true the very moment it no longer worries about adhering pedantically to the empirical, which is often more deceptive than the tricks played on us by our imagined memories.

Daniel Barroca personalizes the anonymous. His quest for the unknown and the untraceable emphasises the notion of chance by divesting it from fatality and assembling an array of collective memories. There, in this unspecified and universal rather than singular place, the artist gathers childhood atmospheres and particular clothes, sounds or shapes that are familiar to us because they belong to a time experienced – even if only in our imagination. As Barroca takes us back to a collective childhood – a childhood we might not have experienced ourselves but which we have longed (though maybe never hoped) for –, our personal knowledge merges with the vague teachings of popular culture. While digital technology withdraws our present time from the differentiation between truth and verisimilitude, Barroca reminds us that this is a timeless issue because the ambiguity is enshrined in our minds and defines our era. We are brought to believe to have experienced things which, in reality, we do not even remember, but the past lives on in the memory or the heritage devolved to the present time. The rest counts for little.

By blowing up an image and scrutinising its details, Barroca dislocates it from its original context into a new imaginary yet familiar world, a process reminiscent of an induced déjà-vu. When enlarging the detail, the form is lost but the image is gained, a psychological image that tends toward pure vision. Rhythm and atmosphere create a hypnotic, ethereal atmosphere; the fact that it is not evaporating is solely owed to the solid and multilayered matter on the film and on the paper. The drawings shown alongside the videos participate in this quest towards the image freed from the rigidity of form.

Daniel Barroca creates fragments of shared time, which he imprisons once and for all, united by the physical depths of silence and the weight which memory carries with it. Birth and death join in a single circular movement. Silence leaves more room for the image and for reflection, and hence for doubt. When silence makes itself less oppressive, the doubts confound themselves with the hesitation of breathing as so many pauses belonging to this suspended time from which this circularity draws the truth. In Barroca’s videos time is suggested rather than dictated. Contrary to the norm, time is never imposed: it is a fact in and of itself that comes to life in the mind of the viewer rather than the mere representation of a fact. Images appear in fragments without adhering to an affected and self-referential narrative in what seems like an updated variation of the classic tastes of the avant-gardes, where the artist plays with confused geometries, which are always in harmony whenever they inhabit nature. Barroca’s collage of found material is not merely an appropriation but a poetic reprocessing that makes it idiosyncratic. It is at once utterly personal and thoroughly general – public intimacy.

As we watch Daniel Barroca’s work, we re-experience sensations from a forgotten yet present time. Rather than an event, we are watching a video that shows a condition, our gaze as unstable and hesitating like the camera movements – true, as it were. What matters is no longer that which is being told, but that which we are able to imagine or recover: sights of particular states of mind where we are gratified from the lack a solution.

in:

Soldier Playing with Dead Lizard, Künstlerhaus Bethanien

ISBN 3-932754-96-4

NUOVI RICORDI

Francesco Stocchi, 2009

L’universo di Daniel Barroca è abitato da presenze sospese, fluttuanti fra due tempi, non meglio definite ma con un’immagine. E’ questa la ricerca verso cui Barroca sembra interessato, il rapporto tra forma e immagine, dove quest’ultima si ritrova proprio nella fuga della prima. Una ricerca nobilitata dall’assenza di soluzione, quindi senza una fine ma con un obiettivo, che non guarda al giusto o allo sbagliato ma s’interessa solo al vero. Un ciclo continuo scandito dall’animo dell’artista, dettato dalle sue esigenze e da quelle presenze che abitano un’universo fatto di nuove ripetizioni, illusioni temporali, sdoppiamenti, dettagli, echi. Echi visivi e sonori dall’origine incerta, forse mai pronunciata. Reminiscenze di qualcosa che forse non è mai successo. Reale ed irreale si confondono in un unico ricordo che diviene vero dal momento in cui è senza preoccuparsi della pedante aderenza all’empirico, spesso più illusorio degli inganni a cui ci sottopone la nostra memoria fantasiosa.

Daniel Barroca personalizza l’anonimo. La sua ricerca verso lo sconosciuto e l’irrintracciabile eleva il valore del caso sdoganandolo dalla fatalità e creando una collezione di memoria collettiva. Lì, in quel luogo non meglio definito, più universale che speciale, si ritrovano certi ambienti dell’infanzia di ognuno, o certi vestiti, suoni, certe forme che ci appartengono perché figlie di tempo vissuto, anche se solamente immaginato. Riconducendoci ad un’infanzia collettiva, forse mai sentita ma sospirata, o magari mai sperata, le conoscenze personali si fondono con ciò che ci è stato insegnato confuso alla cultura popolare. In un presente che attraverso il digitale sfugge alla divisione vero-verosimile, Barroca ricorda che questa è materia classica perché l’ambiguità vive nella nostra mente e scandisce il nostro tempo. Ci si convince di aver vissuto ciò che in realtà non ricordiamo, ma il passato vive nella memoria o nell’eredità che ha lasciato al presente. Il resto conta poco.

Nell’ingrandire fotografie analizzandone i dettagli, l’immagine viene sottratta al suo contesto per appartenere ad un nuovo immaginario conosciuto. Un pò come un dejà vu indotto. Con l’ingrandimento del dettaglio si perde la forma ma si guadagna in immagine, un’immagine psicologica che tende alla purezza di visione. Il ritmo e l’atmosfera portano un carattere ipnotico, etereo, e se non vola via è solo grazie ad una materia solida, stratificata, presente sia nella pellicola che nel foglio di carta. I disegni accompagnano i video in questa ricerca verso l’immagine liberata dalla rigidità della forma.

Barroca crea frammenti di un tempo condiviso e li imprigiona una volta per tutte, uniti dallo spessore fisico del silenzio ed il relativo peso che con esso porta la memoria. Nascita e morte si fondono in un’unica circolarità. Nel silenzio c’è più spazio all’immagine e alla riflessione, quindi al dubbio. Quando il silenzio non suona così pesantemente, il dubbio si confonde all’esitazione di respiri, pause appartenenti a quel tempo sospeso, dal quale questa circolarità trae verità. Nei video di Barroca infatti il tempo viene suggerito e non dettato. Contrariamente alla norma, il tempo non è imposto, essendo il fatto in se che viene creato nell’animo dello spettatore e non una rappresentazione del fatto stesso. Le immagini appaiono in frammenti senza aderire ad una narratività troppo sesso vezzosa e auto referenziale. Una tecnica aggiornata sul gusto classico delle avanguardie dove l’artista gioca con confuse geometrie, sempre armoniche quando abitano in natura. Un collage di materiale trovato ma non una mera appropriazione, bensì rielaborazione poetica per farlo proprio. Personalissimo e alla portata di tutti, un’intimità pubblica.

Noi guardiamo ri-vivendo sensazioni di un tempo dimenticato, ma pur sempre attuale. Non vediamo un video che mostra un avvenimento ma una condizione e il nostro sguardo è realmente incerto, tentennante, come i movimenti di camera. In una parola, vero. Non è più tanto ciò che si racconta, ma più quello che riusciamo ad immaginare o a ritrovare. Vedute di stati d’animo dove ci si compiace dell’assenza di soluzione.

The Archaeology of the Reproduction, Thomas Wulffen

THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF THE REPRODUCTION

Comments on the work of Daniel Barroca

Thomas Wulffen, 2008

translated by Lucinda Rennison

Initially, it may seem rather strange to refer to the reproduction. Surely the category of the image is primary to the reproduction? This could also mean that the archaeology of the reproduction, essentially, is constructed on the archaeology of the image. Because of this, it is necessary to draw a distinction between image and reproduction that shifts the focus away from the archaeological moment. However this kind of difference can be presented more clearly through reference to a concrete object; the work of Daniel Barroca offers such a concrete basis.

Those who visit his studio overlook things in a double sense of the word. They overlook the studio, which makes it possible to identify the space as a place of work. Drawings hang on the walls; black outlines on white sheets of paper. A number of the paper sheets lie on the floor, others are fastened to the walls. But they also overlook the other part of his oeuvre, which employs different forms of presentation. On the big tables, there are a computer and an apparatus for scanning images. At first glance, one seems to be unconnected to the other. But in fact Barroca works in a transmedial fashion. In this context, the word transmedial is merely used to signify the fact that the artist very consciously crosses the boundaries of appearance as transmitted through media.

At this point, it is possible to implement a distinction that grasps the terms quite literally: i.e. the distinction between manufacture and technology. The drawings are part of manufacture, while the invisible moment in the studio belongs to the field of technology. The drawings are objects of manufacture, produced by hand. The objects of technology are less visible, only the apparatus for their visualisation meets the eye.

Barroca works on the narrow threshold between visibility and invisibility. This confrontation has direct bearing on the question of archaeology – in the true sense, and also from the perspective that Foucault developed and applied this concept to. A specific visibility thus becomes clear in the studio space; one that simultaneously discloses and covers up. Let us return to our question at the outset: Where are the images and where the reproductions? The division between these fields is now more straightforward: the aforementioned drawings are images, while the loops in the video apparatus are reproductions. This becomes clear in abstraction to a small detail. This same detail can be found in the cycle The Sequences of Memory, Silence and War (2002/03). In part, the basis for this work is found visual material that Barroca has processed and cut. In 2002, he produced Vestige in this way; it was based on anonymous photographic material that the artist had found in a bookshop in Lisbon in 1998 and 2002. Verdun (2003) employs various film materials from the First World War, while the material of Sarau – dating from the same year – is a direct pointer to Portugal’s colonial past. In the process, the film is quasi dismantled, or a film is produced from photo material. However, this means that the material’s inherent presentation principle is foiled, just as in the motion loops.

The artistic principle of archaeologising images is revealed here. In the film Barulho #1 (Noise) (2005), the film images are covered in a layer that gives them an artificial patina, so to speak.(1) But this layer is also a kind of painterly artefact. In this context, the artist writes: “I have been attempting to establish relationships between two distinct media – the photographic image and drawing – in order to formally trigger a reflection on the mechanisms of the formation of sensibilities.”(2) Two different processes of the archaeologising moment are thus confronted; the inherent aspect of the reproductive material and the external aspect in the artist’s act of processing. Both aspects have an impact on the viewer’s possible experience when observing these works. Barroca’s comment here: “My point of departure is my acknowledgment that in contemporary times experience is becoming gradually poorer, and that images are but a distorting filter of the real meaning of things. […] I engage myself directly with the tensions that occur between photographic records as a means of memory, and drawing, understood as a process of formation of the I.”(3) In addition to this, however, the archaeology of the reproduction also incorporates the perspective of the viewer. That is already obvious from the title Verdun. The younger generation may not be able to make much of this place name, certainly, but the site of the bloodiest battle of the First World War is not reproduced in the film. Instead, Barroca places material in the viewer’s hands, onto which the latter is able to project his own images. After all, film images of war are still readily available, and images from Apocalypse Now stick in our minds. Because Barroca veils these images, their impact is all the more intense, for the identification takes up our own images without resolving anything.

In the year 2007, Barroca began a new cycle of works both surprising and convincing in their radical nature. He turns away from those works based on documentation in order to create documents of a specific kind himself. The circle is completed at this point, for he develops a fresh link to his drawings with the cycle Artefact.

The basis for each individual artefact – which he consciously refuses to present as sculptures – is clay; the artist kneads and photographs this at various stages of his work. His forms of presentation encompass video, positive slides and black and white prints (gelatine-silver prints) as well as discrete traces of the material: the clay leaves marks on the paper, and at this point the drawing appears to develop into three-dimensional space. In the photographic prints in particular, image and reproduction receive a specific materiality that advances further than the concrete medium in which the image appears. It is quite possible, however, that the question of the type of medium cannot be answered but only disclosed: in the artefact.

(1) Here, the artist passes through stages of technical development as a matter of course; from Super 8 to digital video to PAL.

(2) http://www.bethanien.de/kb/index/trans/de/page/artist/id/84

(3) s.a.

in:

BE#15, Künstlerhaus Bethanien

ARCHÄOLOGIE DES ABBILDS

Bemerkungen zum Werk von Daniel Barroca

Thomas Wulffen, 2008

Die Rede von einem Abbild erscheint auf den ersten Blick seltsam. Ist nicht die Kategorie des Bildes primär gegenüber dem Abbild? Das könnte auch bedeuten, dass eine Archäologie des Abbilds wesentlich auf einer Archäologie des Bildes aufbaut. Deswegen muss eine Unterscheidung zwischen Bild und Abbild gezogen werden, die das archäologische Moment in den Hintergrund rückt. Eine derartige Differenz aber lässt sich klarer darstellen an einem konkreten Objekt. Das Werk von Daniel Barroca bietet diese konkrete Basis an.

Wer sein Atelier besucht, der übersieht im doppelten Sinne des Wortes. Er erhält eine Übersicht im Atelier, die den Raum als Werkstatt identifizierbar macht. An den Wänden hängen Zeichnungen, schwarze Konturen auf weißen Blättern. Zum Teil liegen die Blätter auf dem Boden, manche sind an den Wänden befestigt. Aber er übersieht auch den anderen Teil des Werkes, der differente Präsentationsformen nutzt. Auf den großen Tischen stehen ein Computer und ein Gerät zum Einscannen von Bildern. Auf den ersten Blick scheint das eine nichts mit den anderen zu tun zu haben. Doch tatsächlich arbeitet Barroca transmedial. Das Wort transmedial soll in diesem Kontext nur bedeuten, dass der Künstler sehr bewusst die Grenzen medial vermittelter Erscheinung übertritt.

An dieser Stelle lässt sich eine Unterscheidung anbringen, die die Begriffe beim Wort nimmt: Wir meinen den Unterschied zwischen Manufaktur und Technologie. Die Zeichnungen sind Teil der Manufaktur, während das nicht sichtbare Moment im Atelier dem Bereich der Technologie angehört. Die Zeichnungen sind Objekte der Manufaktur, mit der Hand erstellt. Die Objekte der Technologie sind weniger sichtbar, nur deren Apparate zur Sichtbarmachung fallen auf.

Barroca arbeitet auf dem schmalen Grat zwischen Sichtbarkeit und Nichtsichtbarkeit. Diese Gegenüberstellung betrifft direkt die Frage der Archäologie – im eigentlichen Sinne und auch in der Perspektive, die Foucault unter diesem Begriff entwickelt hat. So wird im Atelierraum eine spezifische Sichtbarkeit deutlich, die offen legt und gleichzeitig verdeckt. Kehren wir zu Ausgangsfrage zurück: Wo sind die Bilder und wo die Abbilder? Die Trennung zwischen diesen Bereichen fällt jetzt leichter: Die erwähnten Zeichnungen sind Bilder, während die Loops im Video Abbilder sind. Das wird in der Abstraktion auf einen kleinen Ausschnitt deutlich. Dieser Ausschnitt findet sich dann auch wieder in dem Zyklus The Sequences of Memory, Silence and War (2002/03). Grundlage dafür ist zum Teil gefundenes Bildmaterial, das von Barroca bearbeitet und geschnitten wurde. Im Jahr 2002 entsteht so Vestige, beruhend auf anonymem Fotomaterial, das der Künstler 1998 und 2002 in einer Buchhandlung in Lissabon gefunden hatte. Verdun (2003) verwendet unterschiedliches Filmmaterial aus dem Ersten Weltkrieg, während Sarau aus dem gleichen Jahr mit dem Material direkt auf die koloniale Vergangenheit Portugals verweist. Dabei wird der Film sozusagen aufgebrochen oder aus Fotomaterial ein Film hergestellt. Das aber bedeutet, dass deren inhärentes Präsentationsprinzip hintertrieben wird, ebenso wie in den Bewegungsloops.

Hier offenbart sich das künstlerische Prinzip der Archäologisierung von Bildern. Im Film Barulho #1 (Lärm) (2005) werden die Filmbilder durch eine Schicht abgedeckt, die ihnen sozusagen eine künstliche Patina gibt.(1) Diese Schicht ist aber auch eine Art malerischer Artefakt. Der Künstler schreibt dazu: „Ich habe versucht, Beziehungen zwischen zwei verschiedenen Medien – dem fotografischen Bild und der Zeichnung – herzustellen, um über die Form eine Überlegung hinsichtlich der Entstehungsmechanismen von Sensibilitäten in Gang zu setzen.“(2) So treffen zwei verschiedene Prozesse des archäologisierenden Momentes aufeinander, der inhärente des Abbildmaterials und der externe in der Bearbeitung des Künstlers. Beide Momente wirken auf die Erfahrung, die der Betrachter vor diesen Werken machen kann. Dazu Barroca: „Mein Ausgangspunkt ist die Erkenntnis, dass in der heutigen Welt Erfahrungen allgemein weniger intensiv sind und dass Bilder wie Filter funktionieren, die den wahren Sinn der Dinge verzerren. […] Ich beschäftige mich unmittelbar mit den Spannungen, die zwischen fotografischen Aufnahmen als Gedächtnisstützen einerseits und dem Zeichnen als einem Prozess der Bildung des Ichs andererseits entstehen.“(3) Archäologie des Abbilds aber bezieht darüber hinaus auch die Beobachterperspektive ein. Das wird schon am Titel Verdun deutlich. Zwar mag eine jüngere Generation mit dem Ortsnamen wenig anfangen können, aber der Ort der blutigsten Schlacht des Ersten Weltkriegs kommt in diesem Film nicht zur Abbildung. Eher gibt er dem Betrachter Material an die Hand, auf das er seine eigenen Bilder projizieren kann. Schließlich sind die Filmbilder aus Kriegen keinesfalls ausgegangen, und Bilder aus Apokalypse Now sind noch in Erinnerung. Weil Barroca diese Bilder verschleiert, wirken sie umso stärker, denn die Identifizierung greift auf eigene Bilder zurück, ohne zu einer Auflösung zu kommen.

Im Jahr 2007 beginnt Barroca mit einem neuen Werkzyklus, dessen Radikalität überrascht und überzeugt. Darin wendet er sich von den auf Dokumenten basierenden Arbeiten ab, um selbst Dokumente besonderer Art herzustellen. An dieser Stelle schließt sich ein Kreis, weil mit dem Zyklus Artefakt wieder ein Anschluss an die Zeichnungen gelingt.

Grundlage für die einzelnen Artefakte, die bewusst nicht als Skulpturen begriffen werden sollen, ist Lehm, der vom Künstler geknetet und in unterschiedlichen Stadien fotografiert wird. Die Mittel der Darstellung umfassen dabei Video, Diapositive und Schwarzweiß-Abzüge (Gelatin-Silber-Prints) sowie diskrete Materialspuren: Der Lehm hinterlässt Abdrücke auf dem Papier, und die Zeichnung scheint hier Raum zu werden. Besonders in den Fotoabzügen gewinnen Bild und Abbild eine spezifische Materialität, die das konkrete Medium, in dem das Bild erscheint, hinter sich lässt. Aber es mag durchaus sein, dass die Frage nach der Art des Mediums nicht beantwortet, sondern vielleicht nur aufgezeigt werden kann: im Artefakt.

(1) Dabei überschreitet der Künstler ganz selbstverständlich technologische Entwicklungsschritte, von Super 8 zu Digital-Video auf PAL.

(2) http://www.bethanien.de/kb/index/trans/de/page/artist/id/84

(3) s.o.

(Für die Übersetzung Originalzitate auf Englisch):

Zu (2) „I have been attempting to establish relationships between two distinct media – the photographic image and drawing – in order to formally trigger a reflection on the mechanisms of the formation of sensibilities.“

Zu (3) „My point of departure is my acknowledgment that in contemporary times experience is becoming gradually poorer, and that images are but a distorting filter of the real meaning of things. […] I engage myself directly with the tensions that occur between photographic records as a means of memory, and drawing, understood as a process of formation of the I.”

in:

BE#15, Künstlerhaus Bethanien